Bjarke Ingels on why architecture should be more like Minecraft

It's Ingels' moment. The architectural prodigy's commissions range from Google's HQ to the new World Trade Centre - all united by his philosophy of 'Yes Is More'

[I was very fortunate to have the chance to meet Bjarke Ingels at his HOT TO COLD event at the Taschen book store in Soho, New York. The room was completely packed, so instead of heading to the stage he quickly jumped onto one of the central book islands in front of me, microphone in hand, and began his passionate lecture of hedonistic sustainability and hybrid buildings (or BIGamy as he calls it). Following the speech, I rushed to get my book signed by the notorious B.I.G., and as the room was insanely hot by that time with so many people in the room I offered Bjarke a refreshing beer from the bar. His eyes showed similar relief to a castaway finding water, thus hopefully cementing my name in Bjarke's memory.

[Enjoy the following article, originally on Wired, about Bjarke and his journey of becoming a "starchitect" while transforming BIG into an international icon of cool architecture, and how we should attempt to build a world we want to inhabit, just like a kid in Minecraft]

Just after midday on a cloudy June afternoon, a few hundred architecture aficionados are filing into the lecture theatre at the Royal Geographical Society in London, to see Bjarke Ingels.

Inside, the atmosphere is buzzing - right now, the Dane is the closest the discipline has to a rock star. His international practice, Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), recently finished its first New York skyscraper, and is working on two more, including a proposed second tower at the new World Trade Center. It lists clients from Google to LEGO to the restaurant Noma; commissions that, for most architects, would be career-defining. Yet Ingels is just 41 years old.

He is also a showman. In 2009, Ingels published his design manifesto, Yes is More, as a graphic novel. Its oft-quoted principles, include "BIGamy" (that buildings should have hybrid functions, such as a waste-to-energy power-plant topped with a ski slope, under construction in Copenhagen), and "hedonistic sustainability" (that for green design to succeed, it must be more desirable than the status quo), have made him a popular conference speaker.

Dressed in his regular uniform of a black Acne suit over a long-sleeved T-shirt, Ingels looks tired. He was up late overseeing the final touches to BIG's latest project, the Serpentine Gallery's annual summer pavilion in Hyde Park. The pavilion is the latest indicator of Ingels' "starchitect" status: previous honourees include Frank Gehry, Daniel Libeskind and the late Zaha Hadid. BIG's design, which Ingels calls "the unzipped wall", consists of 1,802 extruded fibreglass bricks. Solid at its peak, the base has been pulled apart to create a cavernous, twisting internal space. The previous evening, Ingels had posted an Instagram picture of structure captioned “Minecraft” – a reference to the wildly popular block-based game.

“I love computer programmers,” Ingels explains of the design. “They have a very beautiful definition of complexity as ‘the capacity to transmit the maximum information with the minimum data’.” Ingels often uses technology as an analogue for design. He describes architecture as “world craft” - Minecraft for our concrete reality. “A kid in Minecraft can build a world and inhabit it through play,” he tells WIRED. “We have the possibility to build the world that we want to inhabit.”

Ingels is prone to bold ideas and unafraid to articulate them. As his architect mentor (and former employer) Rem Koolhaas wrote inTime magazine: "Bjarke is the first major architect who disconnected the profession completely from angst." Serpentine director Hans-Ulrich Obrist puts it more simply: "Bjarke has never shied away from the big topics of architecture, of society, of life. I guess that's why he called his practice BIG."

That attitude, combined with his prodigious rise, has inevitably led to criticism. Later in the talk, Ingels becomes irritated when an audience member suggest the pavilion's design idea is simplistic - "legible at the expense of complexity".

“I think it’s interesting that there is a suspicion of the ability to express what you are doing as a flaw...To me it is only a strength. If you are not able to transmit what you’re trying to achieve to your collaborators you will only have minions – or morons.”

Soon after, Ingels makes for the exit, briefly posing for pictures with fans. (He follows the advice of his friend, Game of Thronesactor Nikolaj Coster-Waldau: "He just says 'yes', does it, moves on. Done.") As we walk back through Hyde Park, he still seems rankled by the question.

"It's legendary how architectural lectures can be incredibly boring," he says. "Like it's this argument that if you're good at explaining what you're doing, you must be bad at something else. Which is idiotic." Soon, though, his mood brightens. "I think a really strong critical dialogue is actually enjoyable because it allows you to sharpen your points," he says, Does he ever feel vulnerable? "Every time you put a foot forward, you are vulnerable. Especially in architecture, because what you do is by definition public art. It's not like it's inside a museum - it is the museum. So anyone is entitled to an opinion."

He smiles. "Opinions are like assholes: everybody has one."

“Bjarke has never shied away from the big topics of architecture, of society, of life. I guess that’s why he called his practice BIG”

Ingels founded BIG in 2005. The practice quickly gained attention for its bold takes on otherwise ordinary projects, in particular two apartment complexes in Copenhagen's Ørestad district, dubbed the Mountain Dwellings and the 8 House. The latter, named for its double-courtyard layout, incorporates a path for residents to cycle up to the tenth floor.

BIG's rapid success has been built on the foundation of Yes is More. "It's not like we design buildings for architects. We design buildings for people who work in a power plant, people who work in a school, people who run a museum."

Every BIG design starts with deep research into every aspect of a building: its users, its environment, its city. After BIG settles on an initial design, it may iterate dozens of times throughout the development process. Instead of a final, perfect edifice, Ingels says, the process develops a "design narrative" for each project. Sometimes that involves users directly: for a park in Copenhagen, BIG crowdsourced objects from around the world to reflect the international makeup of the local residents. "Every time you make a decision, we reiterate why it is that it makes sense. Why is it relevant? What does it unlock? What does it solve?"

The iterations can occasionally be radical. Take VIA 57 WEST, BIG's New York "courtscraper" - a fusion of European-style courtyard development with a Big Apple high-rise. The building, which opened this year, is a stretched pyramidal peak sloping down toward the Hudson. Clad in white, it has the look of a downed Star Destroyer. Originally, the building featured two peaks, with a spire on the waterfront with its own lobby. "Four months into the process, the client calls me up and says, 'We can't have two lobbies, our running costs are going to be too high'," he says. Another firm might have balked, but not BIG. "So then we said, 'OK, what if we just simply keep the entire south and west, and then we just lift this" - he pinches the air, as if pulling on bread dough - "500 feet?"

The resulting iconic spire was, he says, the result of Yes is More: iterating within confines. "I will bet you a million bucks that if we would have walked through the door on day one with that design, they would have said, 'Are you insane?!' But because we had gone through this journey, and created this new design that was clearly a sibling to what we had already done, they could see that it was actually the answer to their question - and they loved it."

Yes is More, he stresses, is not about simply agreeing to clients' whims. Instead, he says, it's about iterating within an established "design narrative", which is shaped by the architect, but also by a building's inhabitants and its environment.

“I think it’s interesting that there is a suspicion of the ability to express what you are doing as a flaw. To me it is only a strength”

The result also has practical benefits: "It's a form of empowerment," he says. "You empower team members with the source code of what you're doing."

It can be hard to keep up with Ingels. During our conversation, he quotes from Einstein, screenwriting theory, Russian folk tales and the relative merits of monarchy and republican political systems (monarchies favour stability, he says). In particular, he is fond of Charles Darwin. "All of the revolutions that Apple and Steve Jobs reportedly delivered were not actually revolutions - they were rather obvious evolutions. Little steps, combining available technologies in a way that made sense. As William Gibson says, 'The future is already here, it's just unevenly distributed.'"

Architecture's role, he believes, is to redistribute that future. "If you look at the projects that have brought us to where we are now, they are mid-income housing on the outskirts of Copenhagen, rental apartments in New York," he says. "We've always had this principle that no commission is uninteresting. Even the most ordinary of projects can become extraordinary. Rather than reserving architecture for cultural palaces or royal palaces, everything merits careful consideration and accommodation."

2 World Trade Centre, New York. BIG's stepped tower for the World Trade Center site hinges on its off-centre core. The proposal overlooks the memorial and Daniel Libeskind's One World Trade Center, though the building is still awaiting go-ahead for construction

Back at the Serpentine, clouds are forming over the pavilion. Ingels walks through the structure, poring over the final details: the alignment of planks in the walkway beneath the space, the arrangement of internal seating. "I love the moments where you stand here, and it's almost like it's completely transparent," Ingels says. The translucent bricks glow with light, giving the space a sci-fi feel. "It has a sort of warp-speed effect. Zhew!" He carves an imaginary route through space-time with his palm.

The site manager approaches. There is a problem: a contractor has made a mistake during the installation of the floor lights, designed to light the pavilion from within in the evening. The error is barely noticeable if you aren't looking for it, but it is too late to change. "It is incredible," Ingels says, exasperated. "You know, there's basically one way to do it wrong - and that's the way it was done. Totally insane."

After he finishes going over some plans - there's a launch party to finalise, and a film crew from Netflix want to shoot some footage for an upcoming documentary - we walk through the park to a restaurant overlooking the Serpentine. Cyclists and joggers meander along the path. "At the end of the day, the true miracle is just to get people to follow the fucking instructions," he sighs.

The Dryline, New York. The Big U - better known as "The Dryline" - is BIG's response to an open call from Rebuild by Design, a $1 billion federal initiative to repair damage to New York in the wake of hurricane Sandy

Ingels has been thinking a lot about control lately. BIG has expanded rapidly: the practice now employs 220 in Copenhagen and New York, and recently opened an office in London. Its website currently lists 16 buildings under construction, from China to the Faroe Islands. Although Ingels remains the face of the business, he relies on his 11 partners to work across the company's operations. "I make sure it's the best idea that gets taken forward, regardless of who came up with it - whether that's the most brilliant solution or the coolest material."

But, whereas Ingels is evangelical about the principles of Yes is More, architecture can be frustrating. "At the end of the day, we're the ones who get blamed for hiccups in the execution. But we are not the builders," he says. "For example: in 57 WEST we didn't design the apartment layouts, the executive architect did. At that point we were just creating our presence in America, so we didn't have much of a bargaining chip."

During the final construction of the Danish National Maritime Museum in 2014, Ingels was so unhappy with contractors that at one stage he considered cancelling the opening (the issues were resolved at the 11th hour). "It's always like that in architecture. I've never been through a process that wasn't excruciatingly painful. You never have a sense that a building was as good as it could have been. That said, they're pretty goddamned good buildings."

The Serpentine Gallery's annual summer pavilion in Hyde Park, Londo

Clients present further challenges: architecture is slow and expensive, and projects often languish in development for years. At the time of writing, BIG's proposed design for 2 World Trade Center, a $4 billion (£3.1bn), 80-plus-storey creation, is still on pause awaiting financial approval.

"I'm super interested in trying to find ways to increase our control, because we're going to take responsibility for our work," he says. "We're going to die to make it great, no matter what."

Ingels cites Apple, which has become the world's most valuable company in part due to its total control over its products. "I don't think we're going to become a contractor," he explains. "But I do know that I would love to be in a situation where we can follow the idea even further towards its final manifestation."

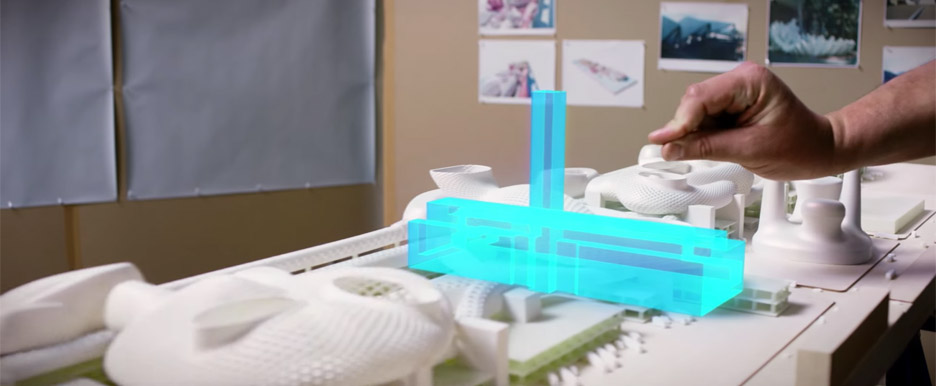

Google North Bayshore, Mountain View. A collaboration between BIG and Thomas Heatherwick Studio, the project incorporates a series of flexible, open-plan geodesic domes linked by parks and cycling paths that snake in and out of the buildings

One element of that plan is BIG Ideas. Launched in 2014, the division is part R&D lab, part incubator for BIG design concepts that can be spun off into independent products or companies. The lab was founded to build the steam-ring generator for the Amager Bakke - the Copenhagen power plant with a ski slope on its roof - which will "puff" every time it emits a tonne of carbon dioxide. It is now working on numerous BIG collaborations and spin-off projects, including Friday, a smart internet-connected lock, "a company that creates water from super-efficient dehumidification", and Urban Rigger - floating student housing for coastal cities built from repurposed shipping containers. The first are scheduled to be built in Gothenberg, Sweden, this year.

Urban Rigger is part of Ingels' vision for where BIG is heading. "My latest obsession is what we call social infrastructure, where we mean it literally - infrastructure that has positive social side effects," he says. "Everybody knows that a highway or bridge or a power plant can have a negative impact on its environment. But what if they could come with premeditated positive social and environmental side effects?"

He points to BIG's Copenhagen energy plant, which will double as a park when it opens in 2017. "It just shows you that with clean technology, a piece of public utility doesn't have to be an eyesore or a lost opportunity. Once the news starts spreading then every facility manager or mayor in the world will start thinking, 'We could have this, or something like this.' And I think that's part of this: spreading the future more generously."

Amager Resource Centre, Copenhagen. Due to open in 2017, this "powderplant" is the epitome of BIGamy: a waste-to-energy power plant. Clad in aluminium bricks and planters, it is designed to look like a green mountain with a snowy peak

Spreading the future, as he explains it, is one reason why BIG has partnered with Hyperloop One, an LA-based company attempting to build Elon Musk's proposal for an ultra-high-speed pod transit system. It is also redesigning Google's Mountain View campus with British designer Thomas Heatherwick, and undertaking projects in Shenzhen, the hub of China's tech industry.

He points to Silicon Valley's increasing investment in "moonshots" - efforts like Hyperloop, SpaceX and Google's self-driving cars. They all have something in common: a penchant for wildly ambitious (some would say overly so) ideas. But, like Ingels, they are all ignoring their critics and simply getting on with building things.

"I think that in the next 20 years the physical world will undergo a lot of the dramatic change that the digital world has seen over the last decade," Ingels says. BIG is poised to shape that transformation. Even virtual and augmented reality, he says, is an opportunity for architecture: the creation of worlds. World craft.

"The engine that has propelled the world economy and innovation - and filled the pages of WIRED - over the last few decades is actually finally getting back into physical space. So I think there is this moment where architecture may again be becoming relevant."

And with that, Ingels stopped talking, and went back to work.

Architect - Tech Writer - 3D Artist - 3D printing enthusiast